The Pool Cal Arts Alumni Magazine Winter/Spring 2020

Front and Back Inside Cover

House & Garden February 2019

House & Garden October 2018

Press

House & Garden September 2018

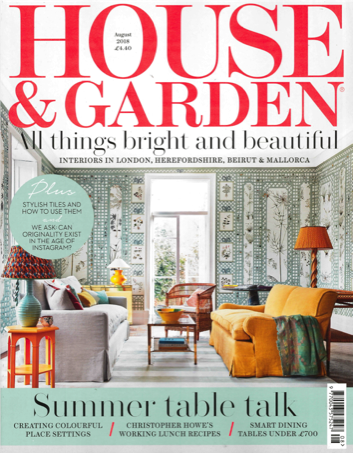

British HG August 2018

LondonLux May 2018

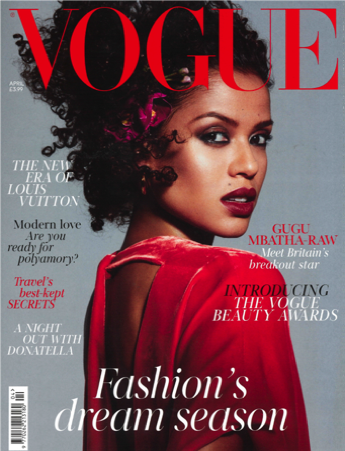

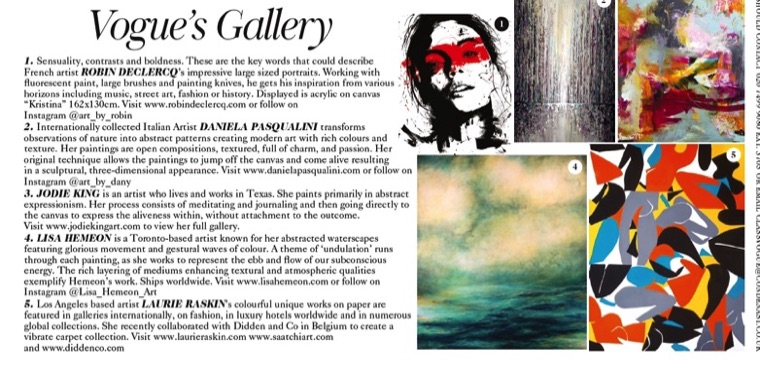

British Vogue April 2018

British Vogue March 2018

British Vogue February 2018

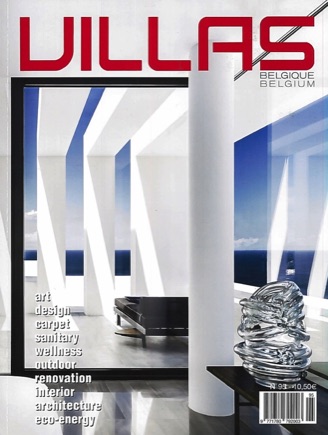

Villas Belgium 2018

Gael December 2018

Paris Match October 2017

Copyright 2008-2024 All rights reserved Laurie Raskin

No part of any of the artworks can be photographed or copied without permission of the artist

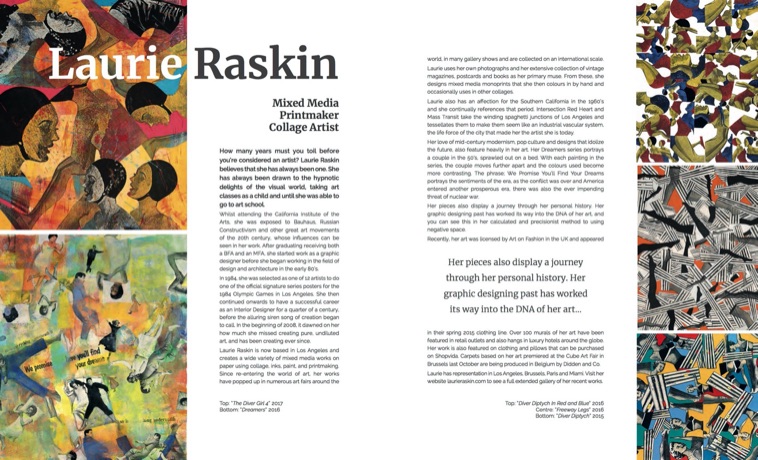

LAURIE RASKIN: MODERN AGAIN

By Peter Frank

We have outlived the modern era, but we have not outpaced it. The drama of modernist aesthetics and the still-stunning glories those aesthetics yielded lurk in the back of our worldly consciousness like the dreams and glimpses of our childhood. Modernism was a radical reorganization of perception, an undoing of the Renaissance as forceful as the Renaissance itself, and its shock waves still resonate. But now, so do its charms, its wit, the inner logic of its inventions. The shock waves are no longer shocking, but simply stimulating.

In the post-modern era, some artists are more stimulated than others — although as we re-discover this item or that factor in modernism’s history, the movement’s intricacy and range of possibility become more and more credibly renewable, recyclable, reinterpretable. At this point, an artist can “look like” Picasso in order to determine what escaped Picasso, not just what fed him. For an artist like Laurie Raskin, resemblances are evident, even obvious, and secondary to her exploration of modernism itself. The art Raskin makes pays homage to the art of fifty or a hundred years ago, but does not imitate it; rather, it spins new art out of old artistic DNA.

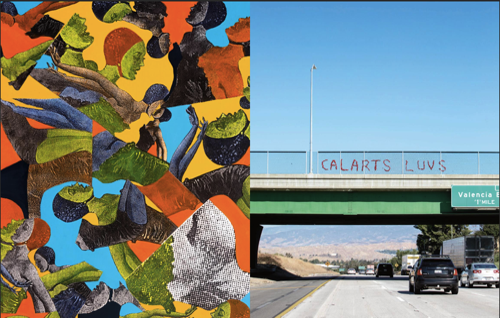

At present Raskin works in two modes, both of them readily recognizable as couched in modernist formal language and thinking. One mode in effect reconsiders the late work of Henri Matisse from the other side of Abstract Expressionism; the other looks back at the Bauhaus from the “position” of Pop Art. The modernist reach, spanning decades, collapses in Raskin’s approach into a visual experience that indeed feels hybrid, but also feels integral: she draws out the visual essences of high-modernist phenomena by finding their echoes in late-modernist practice. Henri Matisse’s spare yet extravagant cut-outs become rich and complex canvases, full of restless energy, when translated into what looks like gestural abstraction. In fact, Raskin’s crowded, colorful paintings are not at all gestural; they are as clearly and flatly limned as those ultimate masterpieces of Matisse, and as calculated in their composition. But they burgeon with Abstract Expressionist brio.

Sight unseen, it would seem something of a joke to run Matisse through 1950s abstraction. But his cutouts were themselves “1950s abstraction,” and his overarching oeuvre was universally embraced by gestural painters on both sides of the Atlantic. In bringing the spirit of Matisse to the visual realm of action painting, Raskin is not attempting the absurd, but reconfiguring history, and not that radically. Finding commonality, even harmony, between her sources here, she determines an abstract style as distinctively hers as it is distinctively modernist.

Raskin’s non-abstract style is no less faithfully modernist, and is again sourced in the conflation of high- and late-modernist tropes. Raskin, a former designer, has a particular fondness for the Bauhaus style, most particularly in graphic design and photography — and notably in and with collage. Instead of Matisse’s “pure” collaged shapes and colors, here Raskin emulates central European photomontage, that of the Bauhaus not least. Her rhythmic compositions recall Moholy-Nagy; her clustered figures and buildings suggest Paul Citroën; the tumble of incongruously paired clippings conjures Russian constructivists such as Lissitzky and Rodchenko.

But if quotidian reality invades the space of abstraction through collage, in Raskin’s work as in her predecessors’, it does so here in a manner that brings attention to the nature of the “invasive” imagery. The artists and designers of inter-war Europe devoted themselves to the creation — imposition, if you will — of a harmonious environment. The visual language of postwar America, on the other hand, strove to determine, influence, and exploit a social status quo, an environment determined not by the artist’s vision but by the consumer’s appetite. This was the subject of the implied critique Pop Art brought to artistic discourse in the 1960s. This, too, was the issue in the air, the “Mad Men” issue, during Raskin’s own childhood — making her a consumer of Pop Art. As an adult, she came to “consume” the Bauhaus as well.

Raskin’s collage and collage-like work features not only Bauhaus and Pop qualities, but those of Cubism on the one hand and Pattern & Decoration on the other. To a certain extent, these two disparate movements — one core modernist, the other crucially post-modernist — also recur in her painterly Matisse-meets-action-painting work. The brittle rigors of Cubism, which shivered the boundaries of the real to free time from its linearity, seem light years away from the self-consciously beautiful and surface-affirming manner of Pattern Painting. But both isms rely on an entirely reformulated concept of structure, thus in their own ways upending given notions of design on a plane.

What Laurie Raskin has done is to reconsider modernism, and even its post-modernist echoes, as design on a plane — design in which pictorial incident can co-exist, even interact, with entirely self-contained formal elements. The real and the imagined, the banal and the beautiful, occupy the same optical realm and even interact so as to modify one another. The modernists, we suppose, preached purity — purity of intent, purity of content, purity of purpose. But in fact modernism wrestled continually with the contradictions and complexities of life, it did not reject or ignore them. The heterogeneity rampant in Raskin’s oeuvre not only provides room enough for the concurrence of disparate elements, but reflects in such syncresis the ambition of the modernist project itself.

Los Angeles

August 2019

Laurie Raskin Modern Again

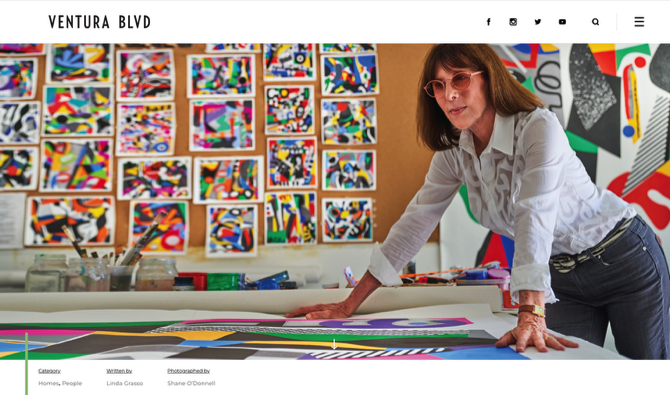

Ventura Blvd